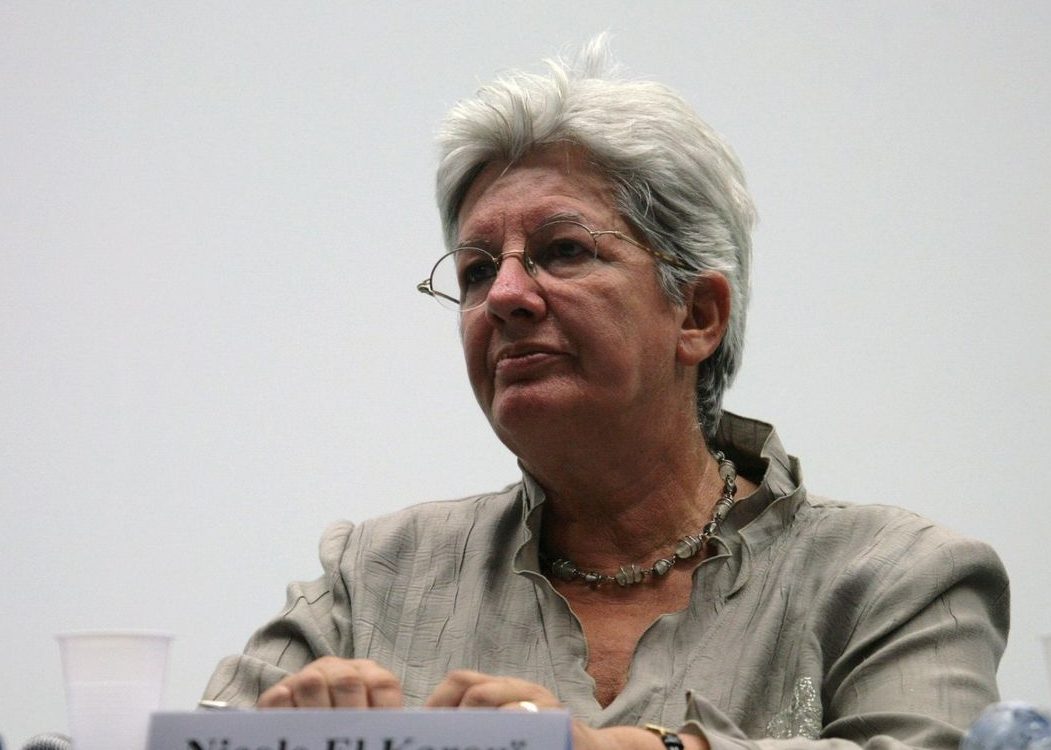

Between Mathematics and Finance: an interview with Nicole El Karoui

Interview by Sema Coskun, editing by Francesca Arici and Anna Maria Cherubini

- Born inFrance

- Studied inFrance

- Lives inFrance

Interview

Nicole El Karoui, Professor Emeritus at Sorbonne, is one of the pioneers of financial mathematics in France and the initiator of a Master which is considered one of the most influential in the financial world.

When have you decided to become a mathematician and how?

My decision has been somewhat influenced by the structure of the French academic system. After the baccalaureate, I was undecided between philosophy and mathematics but ended up choosing for science. After attending the classes préparatoires aux grandes écoles, I returned to the teacher training college, which in 1964 offered separate training for boys and girls. During my master’s degree, I had probability classes that I found incredibly engaging and that’s what pushed me to specialize in that field. In 1968, around the same time that the student movement had frozen France for a month, I decided to reach out to the probabilist Jacques Neveu and ask him for a thesis. He gave me a research article to read and asked me to come back in a month to discuss it with him. This article was almost impossible for me to read at the time, as it was based on very recent results in probability. Luckily, I had two friends who were more experienced and who offered to read the paper together: that was a very formative experience. We formed a working group where we saw each other every day to work on research. This is how I realized that everyone has their way of doing maths.

We formed a working group where we saw each other every day to work on research. This is how I realised that everyone has their way of doing maths.

This experience was the most important for me as a researcher because it taught me how to do mathematics.

In the late 1980s, you co-founded, together with Helyette Geman, the master programme in quantitative finance which is commonly known as the “DEA El Karoui”. Since then, you shaped how quantitative finance is taught in French academic institutions. Which was your motivation at the beginning of the process?

Various events in my career have contributed to this. In 1973 I was appointed to the Université du Mans as a Professor. It was a small and young university where my colleagues and I had to build the research teams and the teaching program from scratch. This was a very interesting and formative experience for me, especially given my young age at the time. I set up a working group on stochastic optimization, with several women including Monique Jeanblanc and Monique Pontier: it was mainly very theoretical work. Then in 1981, it was decided that the École Normale Supérieure should be mixed gender. As the conditions of selection were more adapted to the competitive spirit of the boys, we were against this decision. We were worried that the total number of girls would decrease because of the selection criteria were not well chosen. This is indeed what happened, and in some sense, we damaged a system that was, in my opinion, working very well, by applying positive discrimination, which is something I have always been against. At the time there were always 3 or 4 French women as plenary speakers in international conferences, which is no longer the case today. The old setting of the École Normale with separate classes provided a more friendly atmosphere where girls could develop more confidence in their abilities, and led to a higher number of women mathematicians.

The old setting of the École Normale with separate classes provided a more friendly atmosphere where girls could develop more confidence in their abilities, and led to a higher number of women mathematicians.

Then, in 1988 I took a sabbatical which I spent working in a bank because I felt it was good for the students that their teacher had also professional expertise. The young people at the bank were using the Black Scholes equation and I started to get interested in these problems. So it was really by chance that I started using stochastic calculus to solve problems in financial markets. At the end of the semester, I started a collaboration with a friend at the bank on the rate models. Many things were happening in the financial landscape in those years. The Société Générale was visionary in recruiting engineers for technical developments. Banks were starting to look for probabilists specialised in stochastic calculus and able to develop algorithms. It was clear that it was necessary to train young people with this specific profile. So we started this master with 6 students, training them to become quantitative analysts, and also researched theoretical and numerical problems, as it was necessary to develop new fast algorithms to address the increasingly complex models in use.

The master made the connection between the academic world and the financial industry stronger. It’s an adventure that has been going on for 30 years now and it worked, thanks to the new IT and financial market contexts.

The master made the connection between the academic world and the financial industry stronger. It’s an adventure that has been going on for 30 years now and it worked, thanks to the new IT and financial market contexts.

Many quantitative analysts and investment bankers who graduated from your programme hold now top positions. How was it possible to achieve such a big impact on the finance industry?

In the last decade of the century, it had become necessary to develop a lot of research because financial markets were growing fast, as did IT. However, banks were less interested in doing in-house research themselves because their earnings were growing steadily. Our students, with a very good level of maths and numerics, were coveted by international banks. Our internships in banks are focused on solving specific problems, it’s not just spending time in various departments. By opening the Master to foreign students we also gained a lot of new students: the master is not very expensive, especially compared to US masters, and the internship component made it also attractive for students from European countries like Germany and Italy, where Master’s have a more academic flavour.

With your research, you built an important bridge between academia and industry. Having your name on a degree is considered by Rama Cont, a former student and now a well-known professor in mathematical finance, “a magic word that opens doors for young people”. How could you build such a strong tie between the two worlds?

After a while, we realized that for the students it was more attractive to work in a bank than to pursue a Ph.D. were they would be awarded a modest scholarship. In 2005 I met the HR manager of the Société Générale to discuss this issue. I told her that if they were to continue hiring all the good students in 10 years there would be no more professors to train new generations. This led to the formation of a chair funded by the Société Générale that will give good Ph.D. students well-paid scholarships. Thanks to this we had a lot of PhDs doing top research in financial mathematics

Based on your own experience, could you explain how the worlds of academia and finance interact? How does mathematics help the development of instruments for finance and vice-versa?

People in industry may think that academics do not understand anything of the industrial world but the truth is that academics provide a framework and a formalism. One example is the concept of volatility: one may think there is just one type of volatility. In practice there are easily 10 different kinds of volatility: the formalism developed for them has facilitated the interactions between practitioners.

One should keep in mind that a rigorous theoretical framework is necessary to design models. For example, there was an old attitude of not checking numerical codes before using them, thinking that the market would have told if they were working or not. Nobody would dream of doing this in the aeronautic industry.

Moreover, part of the role of mathematics in applications to finance lies in understanding what we can do to update our models taking into account the fast changes in the financial markets. We need rigorous mathematics and at the same time, we need to be sure that our hypotheses work in practice.

A big difference lies in the approach. Financial experts start by simple models that they try to adapt to more complicated situations, whereas in maths the formal frame is usually already set for dealing with the more general case. The advantage of maths is that it is suitable for reformulating problems.

This is how the collaboration with academia can help the markets: mathematicians can warn against wrong approaches. For example, I was very against credit derivatives, because the whole theory says it would not work: the crisis showed that I was right. You have to be modest in the role that maths plays in understanding the markets, but the mathematical formalism says a lot.

Do you have any advice for young mathematicians wishing to work in finance, based on your experience? What is your role as a mathematician?

My group and I were lucky to be the first to join the financial market and we did it very carefully and that’s why it paid off. Once again it is the merit of women who have the patience to do things carefully.

First of all, one needs to be technical enough to be respected, but then one also has to take the time to understand the background and the framework.

My specialty is hedging portfolio markets. We have used maths tools because they are compatible and work well, however, we are currently facing serious problems because we are only able to cover the medium and short-term risks. This clearly does not capture all the information and the approach is partly insufficient. How important are the things which are not taken into account?

In some ways, the organisation of the markets goes against what the theory says, so my role as a mathematician is to say that there is a problem where others do not see it.

Do you have any advice for women mathematicians at the beginning of their careers?

The big advice I would give to young mathematicians is is to do what they are passionate about and not worry about the rest.

For women, I would especially recommend that they do not focus only on their progress in the short term, and they don’t give too much weight to the negative things that can happen in the short term.

In my case, I had children and for years I did not have a lot of time to write articles but if we continue to do things we are passionate about, it will certainly pay off.

Another thing is that it is not necessary to be confined to the woman’s role. For example, in universities, it is often the women who spend time working on educational aspects like degrees, programmes, teaching committees, etc. In my case, I see myself more as a researcher and secondly as an educator. Of course, I have created this master, which works very well… But my advice would be to stay a mathematician and researcher and not be mistaken about priorities.

The most difficult times in mathematical research are when one is thinking a lot about a problem without finding a solution. In these difficult times when research seems not to work, I have often told myself I would have done better to take care of my young children. I know how dangerous this kind of thought can be. My advice is that you should not give up on the research in maths, to stick to your passions and your choices.

A child takes a lot of time so if one chooses of continuing with research while having children, it is essential to be clear: the children will understand very quickly that one we are not 100% at their service.

When I started working in the early seventies, the society was not so used to women working full time, but after the oil crisis, the attitude totally changed. At that time I had 4 children. My message is that If you are coherent and clear in your choices it can work very well.

Research is not a linear process: there are good periods but generally, those do not last long. The competition can be fierce.

Research is not a linear process: there are good periods but generally, those do not last long. The competition can be fierce. My advice for women mathematicians struggling with the competitive environment is to believe in what they are doing, without adopting the boys’ standards. I think academia has to set new, more appropriate standards. Some researchers may not have an awful lot of publications but they can still develop skills that are valuable to the institution they are working in.

I honestly think that I succeeded in finance because I am a woman and because of my inclusive approach. The HR manager of the Société générale made me notice two days ago that boys tend to say “I” while women say “we”. Women leaders in a department tend to make sure that all the members’ progress, while men leaders are more likely to make that one or two stand out. Progress of the group as a whole may be less fast, but in the medium term, it works very well.

Do you have a project or a dream in mind you want to achieve? Which are your passions?

My project is to continue working in finance with a mathematical framework in mind.

My other project is to make sure that girls do science to occupy a place in an increasingly digital world.

There are clear measures that can be taken to make quick changes.

There are clear measures that can be taken to make quick changes. For example, I am in favour of having a minimum quota of 20% of women in research recruitment. Because we need to have enough women to show that this can work. We need women scientists to come out of the shadows. The number of women in science has always been extremely low and it is necessary that we talk about it, not only in our circles but also with the public. For instance, we should talk about it on TV and we need to showcase women scientists in films and talk shows. I put forward an idea: when a project is submitted for a grant, there should be a man and a woman at the head of the project for it to be accepted. If currently the majority of project leaders are men, how do expect things to change? We must fight for this change, which in the end will benefit society as a whole.

* I wish to sincerely thank to Prof. Ahmed Kebaier for his invaluable help to translate the interview from its French version into English.